Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

Macbeth

Auckland Arts Festival

Royal New Zealand Ballet

Co-production with West Australian Ballet

Kiri Te Kanawa Theatre, Aotea Centre

4-7 March

CREATIVE TEAM:

Choreography – Alice Topp Set & Lighting Design – Jon Buswell

Costume Design – Aleisa Jelbart

Dramaturgy – Ruth Little

Music – Christopher Gordon

Conductor – Hamish McKeich

String Ensemble – Musicians of the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra

Then

Dunedin, The Regent, 13-14 March

Christchurch, Isaac Theatre Royal, 18-21 March

Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

The Royal New Zealand Ballet ‘s new Macbeth, is a contemporary interpretation of one of Shakespeare’s most ruthless tragedies which is as relevant now as it was four hundred years ago. As in many of his plays Shakespeare explores the intense, often tragic tension between the individual and the state, showcasing how personal identity, ambition, and morality clash with political power and societal duty. In his plays state authority and sovereignty, demand conformity, yet individuals seek autonomy or challenge the status quo, navigating complex power structures.

He explores the Machiavellian rise to power and the devastation that two individuals can inflict on the state.

This is all achieved in this production through the choreography, the sets and the music.

The sets designed by Jon Buswell are essentially minimalist while the lighting, also by Buswell is more complex. At some points the lighting is focused on the main characters, at other times shadows and darkness dominate.

Created by internationally director / choreographer Alice Topp the ballet unfolds in a ruthless modern world shaped by political ambition, media manipulation and the fatal seduction of power.

She says, “Macbeth is one of Shakespeare’s great tragedies, exploring themes as current today as they were when first written,” says Alice Topp. “An epic story fuelled by political ambition, passion, desire for power and the burden of guilt, its potency endures. Our Macbeth is set in a hierarchy-hungry, high-society city, where political storms, media frenzy and personal ambition collide.”

The music for the work has been composed by Christopher Gordon and features both recorded and live music. One hundred and twenty-nine musicians contributed to the recorded music while an octet of strings from the New Zealand Symphony Orchestra provide live music. The musical landscape provides full orchestral sound with driving, unrelenting tempo that echoes the character’s anxieties.

Gordon created a series of musical themes designed to reflect the characters as well as the mood of the various sequences of the ballet. His complex music consisted of big band music, electric dance music, funk, film music and references to composers such as Phillip Glass.

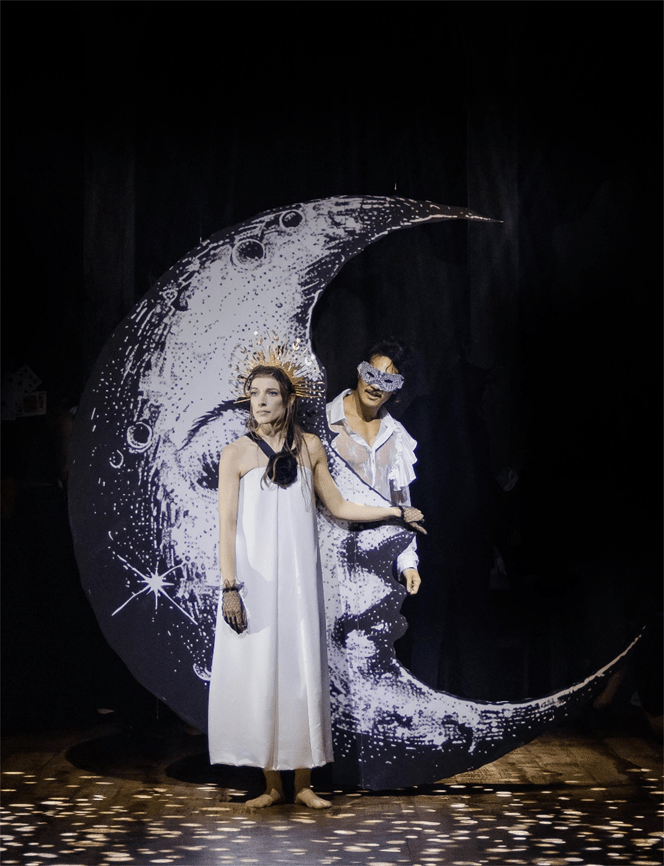

At the centre of the ballet are the two malevolent Macbeths (Brandon Reiners and Ana Gallardo Bobainaw) who dance their solos, pas de deux with moves which indicate corruption and self-centeredness.

The visceral language of the choreography is used to explore the characters psychological pursuit of power and duplicity.

The classical poses and movements which are normally used to display romantic connections were subverted so that these movements create a disquiet which reflects their own inner turmoil. When the two of them dance their elaborate almost ritualistic dances they seem to be abusing each other in erotic displays.

While the sets are minimal, they are often dominated by tables surrounded by protagonists who engage in discussion and planning. These balletic movements around the table recall Canadian choreographer Crystal Pite’s “The Scenario”, her witty take on a boardroom meeting,

As the three witches / influencers Kirby Selchow, Ruby Ryburn, and Shaun James Kelly are an excellent melding of the comic, the supernatural and the intruding media with the endless writhing, gesturing and guttural sounds.

Laurynas Vėjalis as Duncan, Dane Head as Malcolm, and Kihiro Kusukami as Banquo gave strong displays which contrasted with the spikey dancing of Reiners and Bobainaw.

There were a few occasions when the audience was given some indication of the story with texts projected onto screens, including a few lines form the play itself but there were other times when the audience could have been given more useful indications of location and event.