Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

Shane Cotton

New Paintings

Gow Langsford, Onehunga

Until November 16

Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

Shane Cotton has progressively mined the history and myth of Māori along with its intersection with European colonisation, featuring images which recall stories, along with references to historical and mythical figures and locations.

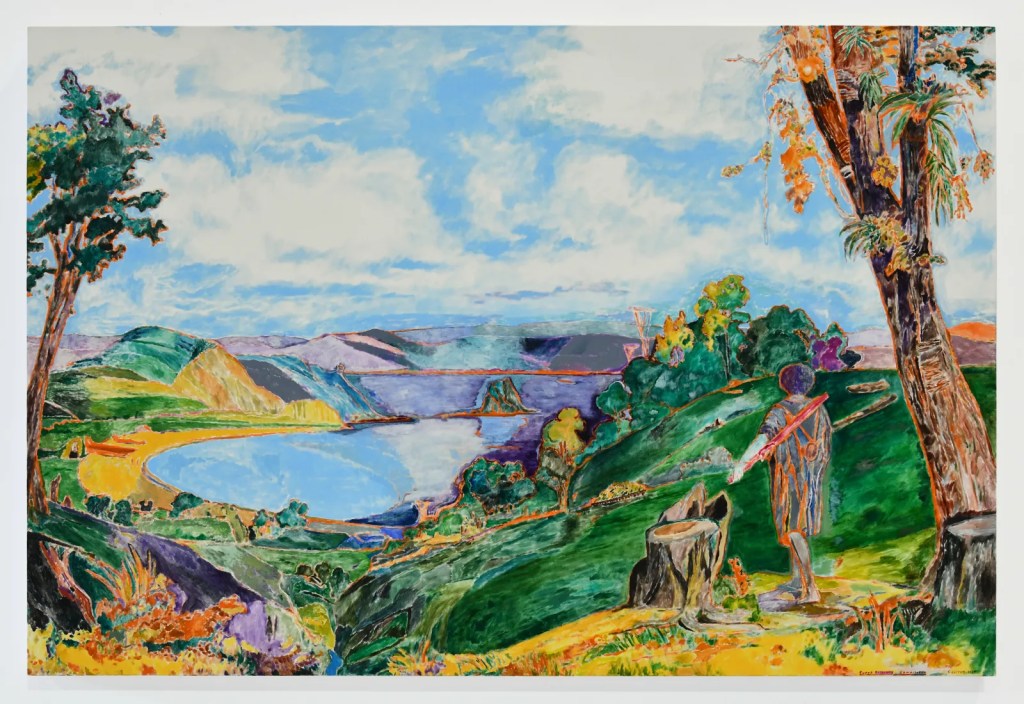

With his latest exhibition of “New Paintings” the artist could be seen as entering his Fauvist period with many of the paintings having the features of the Fauves. Those painters of the early part of the twentieth century employed simplified shapes along with intense and juxtaposed colours.

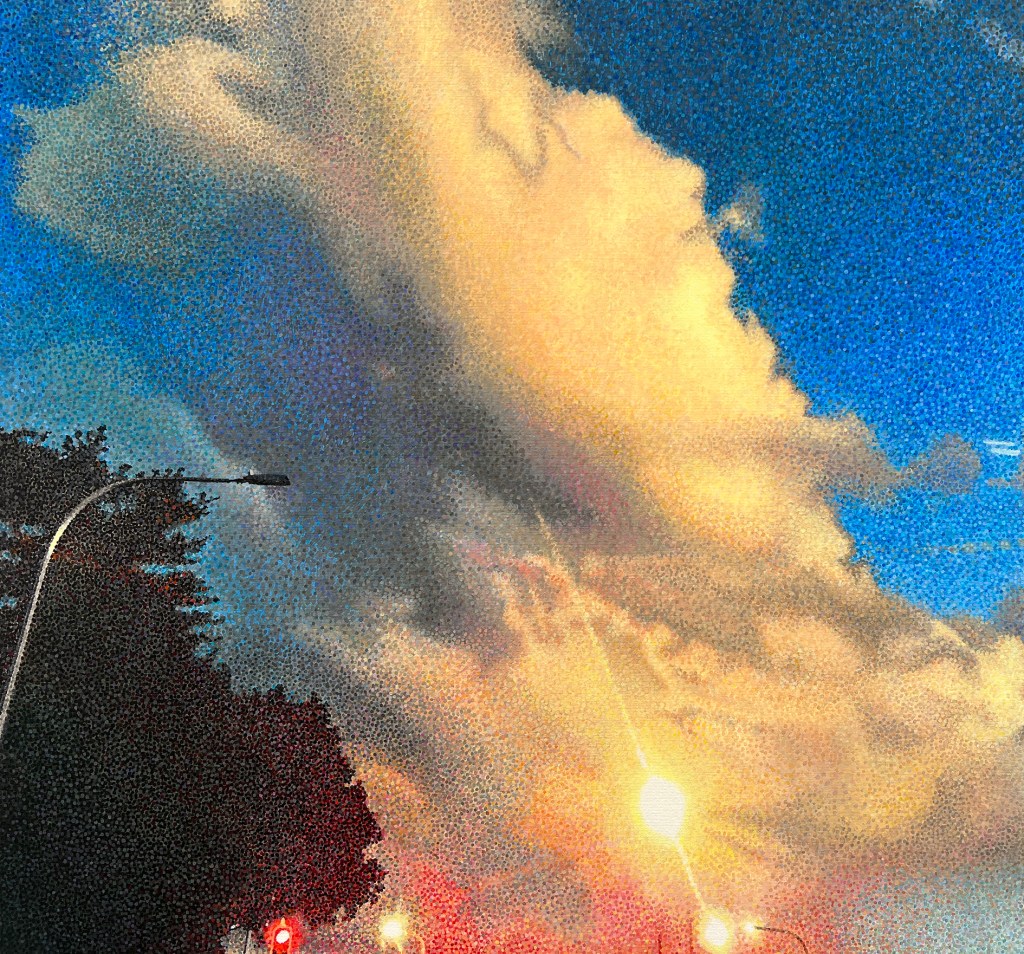

The “He Waka Karaka” ($9000) featuring a small Pacific craft with a sail exemplifies this aspect with intense blues, purples and green while the large, colourful “Super Radiance” ($90,000) is an example of one of the new directions of Cottons painting – more traditional landscape painting. Even though his previous works have featured landscape forms these were generally refined and abstracted.

There are several works of Cotton’s Toi Moko works where the tattooed and preserved ‘shrunken’ Māori heads reference conflict, trade, and repatriations. In works such as “The Great Attractors” ($55,000) the tattoo lines tracing out genealogy are linked to the notion of neural connections, knowledge links and computer networks.

Apart from the shrunken heads Cotton has rarely included figures in his work but in this show, there are several which connect with his living in Northland and revisiting some of his earlier work and the notions of colonialism and cultural exchange.

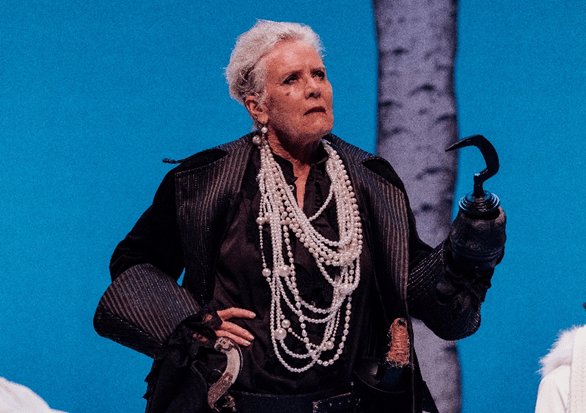

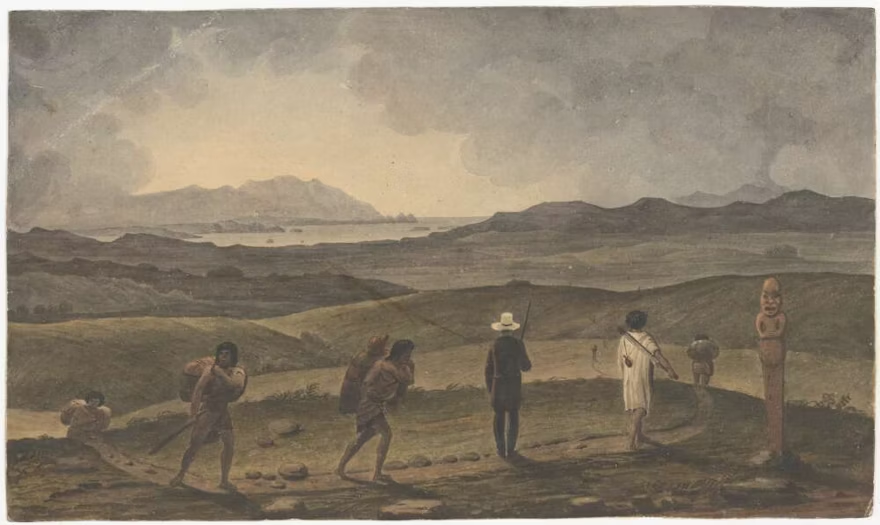

In “The Walker” ($8500) he has replicated the self portrait of the early explorer/artist Augustus Earle taken from Earle ‘s painting “Distant view of the Bay of Island”. Cotton has also appropriated another figure from the work , A Māori with a taiaha who is leading Earle . This figure is also present in “Super Radiance”, “Sunset Gate” ($48,000) and “He tangata hikoi” ($8500) acting as a guide through the landscapes of the North.

Cotton has also used an image of missionary and publisher of Māori works Thomas Kendall taken from the painting “Hongi Hika and Waikato” with Thomas Kendall in England in 1820” by James Barry.

This image is used in the small portrait “Internal Visions” ($8750) and “The Visitation” ($8500) where Cotton has depicted him contemplating a colourful, modernist manaia form where in the original painting he is looking at Hongi Hika and Waikato.

There are also a few of the artists flower painting such as “Insert” ($12,500) which have developed over the years for his early plant paintings.

There are a number of the artist’s three panel works most of which feature a manaia figure flanked by delicate foliage while others have landscape/vegetation panels or in the case of ”Ahuaiti’s Cave” ($130,000) images of the sea. This work refers to the Ahuaiti who was rejected by her husband, forcing her to live in a cave on the Northland coast with her son Uenuku Kuare who is depicted at the base of the painting as a tiny figure, the same image as Earle’s guide in “Distant view of the Bay of Island”.

This linking of mythic figure to historical figure to an invented guide inhabiting some the paintings is an example of Cottons ability to transition across myth, history, time and location.

To subscribe or follow New Zealand Arts Review site – www.nzartsreview.org.

The “Follow button” at the bottom right will appear and clicking on that button will allow you to follow that blog and all future posts will arrive on your email.

Or go to https://nzartsreview.org/blog/, Scroll down and click “Subscribe”