Reviewed by John daly-Peoples

Brahms 3

Auckland Philharmonia

Auckland Town Hall

February 27

Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

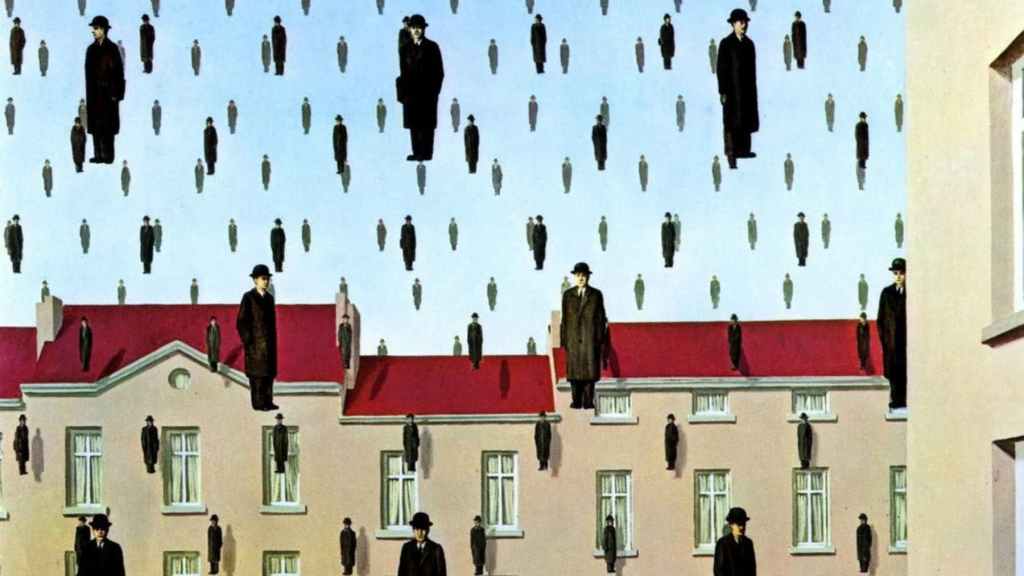

The “Brahms 3”concert began with Romanian composer Gyorgy Legeti’s “Concert Romanesc” written in 1951. The work opens with joyous images of landscape studded with hints of folk music. These passages combined humour and experimentation, qualities which inhabit much of his later music.

From the middle of the piece there were more sombre sounds, as though confronting the history of his country as well as the suffering and death of his parents in Auschwitz during World War II.

As the work became darker and bleaker there was a whirling dance of death moving to a finale where the whole orchestra exploded with lively, suffocating sounds.

Following his performance last week James Ehnes’ performance of Bartok’s “Violin Concerto No 1” was highly anticipated. He did not disappoint. With the soulful opening movement he was initially joined by Andrew Beere and Lauren Bennett before others from the string section joined, adding to the density and complexity of Ehnes’ playing.

Following on from the strings, the woodwinds provided a slightly unsettling voice and even as the orchestra gained in intensity, Ehnes’ violin rose up , soaring above the sounds of the orchestra with some strident sounds which were reflected in Ehnes’ rigid demeanour and exacting playing.

From the second movement on, his playing style changed, taking on a more passionate and expressive approach with some more hectic, gypsy-like playing as he battled against the sweep of the growling orchestra. However, even when he was frantically playing there was a sense of his being totally in control.

With his mastery of the violin, his skilful changes in pace, and tone the audience was treated to a display by a consummate violinist.

While Ehnes received a rapturous ovation for the Bartok it was his encore, Eugene Ysaÿe’s “Violin Sonata No.3 ‘Ballade” .that got a tumultuous reception. The solo work dedicated to the Romanian violinist and composer George Enescu which was beautifully structured requires an intelligent and skilful player – all the qualities that Ehnes was able to bring to the piece.

The big work on the programme was the Brahms “Symphony No 3, a work which is full of marvellous melodies but which is something of an enigmatic work.

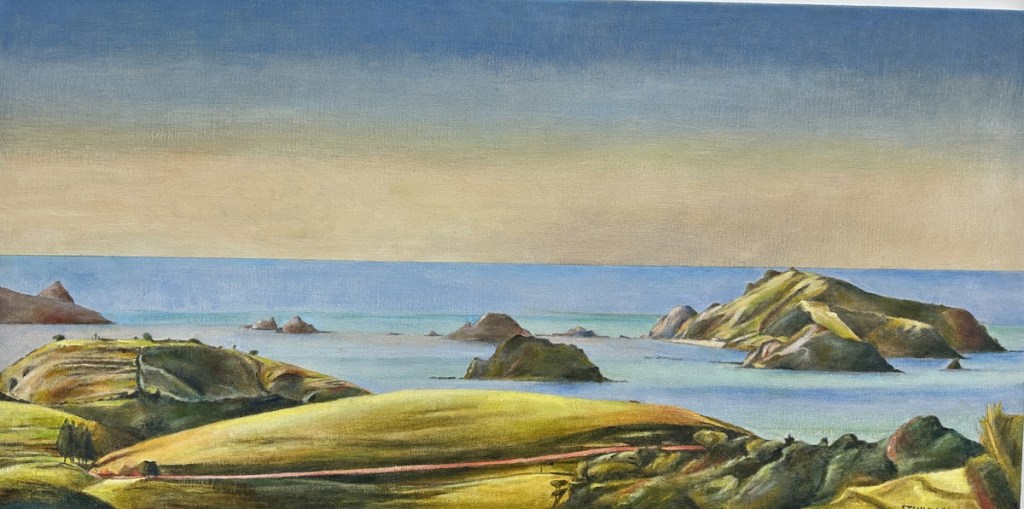

In many ways it is a forerunner of the impressionist works of Debussy and Ravel reflecting the interest of the Impressionist artists of the late nineteenth century. Much of the music is linked to visions of landscape, light and shade, colours and texture.

These images parallel a world of emotions and feelings, the composers inner and exterior worlds mingling. In building a structure based on these links Brahms explores the nature if the human condition. This is very evident in the final movement with its passages of drama and tumult suggesting natural forces as well as the inner turmoil of love and passion.

The final works on the programme, three of Brahm’s Hungarian Dances had Conductor Bellincampi conducting at breakneck speed and while he spent much of his time dancing on the podium the orchestra were swept up by the music and carried along by its own impetus.

Bellincampi used the dances to book-end a farewell to the orchestra’s Music Librarian, Robert Johnson who has worked at the orchestra for over thirty years.

To subscribe or follow New Zealand Arts Review site – www.nzartsreview.org.

The “Follow button” at the bottom right will appear and clicking on that button will allow you to follow that blog and all future posts will arrive on your email.

Or go to https://nzartsreview.org/blog/, Scroll down and click “Subscribe”