Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

Opera Australia

Tosca by Giacomo Puccini

Libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa

Sydney Opera House

July 13

Performances until August 16

Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

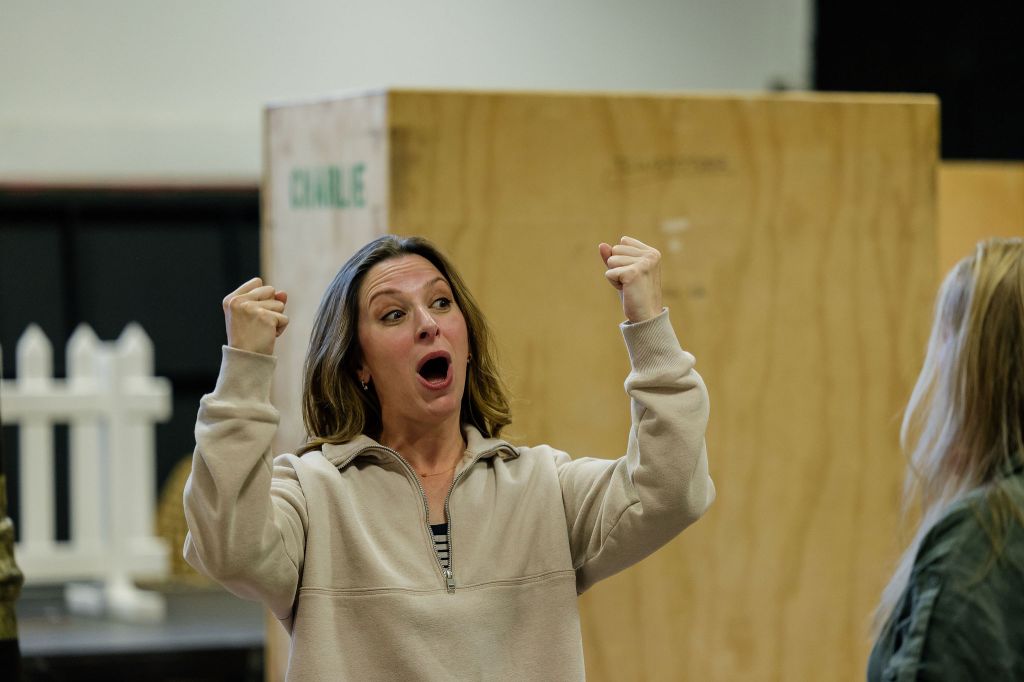

Last Saturday’s performance of Tosca at the Sydney Opera House didn’t go quite as planned. The role of Tosca which had been played by a now ill Giselle Allen was to be replaced with Natalia Aroyan

Allen’s Tosca had previously been reviewed in Limelight where her performance was described as “a wonderfully capricious creation; a haughty, self-absorbed prima donna one minute and tragic heroine the next”.

This was to be Aroyan’s first outing in the role but she has had several roles in other Australian Opera productions and has previously even performed with Dame Kiri te Kanawa.

From the first moment we hear Tosca calling her lover’s name from offstage to her bursting onto the stage any concerns about her abilities vanished. She revealed the power and lyricism the role requires immediately. We also heard the notes of the recurring love theme, sometimes calm, at other times agitated, mirroring Tosca’s changing moods. In this opening scene she also revealed other aspects of her complex nature, playfulness egotism, jealousy and romanticism, giving the audience one of the crucial aspects of the opera – a believable character who, she says “lives for art”.

Her voice in Act II traversed a huge range of emotion, – pure love, pain and yearning while her soaring rendition of the aria“ Vissi d’arte ” captured an almost ethereal dimension.

In a sense she is the alter ego of Puccini who saw the opera a political work which had a strong political thread with a plot that revolved around the historical and political narrative of Italian nationalism. While the opera was originally set in Rome in the early part of the nineteenth century, Director Edward Dick has set the work firmly in the twenty-first century with laptops, CCTV and earpieces. All this provides a very clear reference to the growth of contemporary fascism.

The story , set in Rome still revolves around the tragic love triangle between Floria Tosca , the famous opera singer ; Mario Cavaradossi , a painter ; and Baron Scarpia , the sadistic chief of police .

The opera opens with the escaped revolutionary Angelotti (David Parkin) making a dramatic descent by a rope from the opening in a painted dome in the ceiling of a church. This oculus can be seen as a reference to the ceiling opening of the Patheon in Rome. Cavaradossi comes to his aid and in so doing implicates himself and Tosca in his escape and that knowledge is exploited by Scarpia in order to capture the escaped Angelotti, punish Cavaradossi and seduce Tosca.

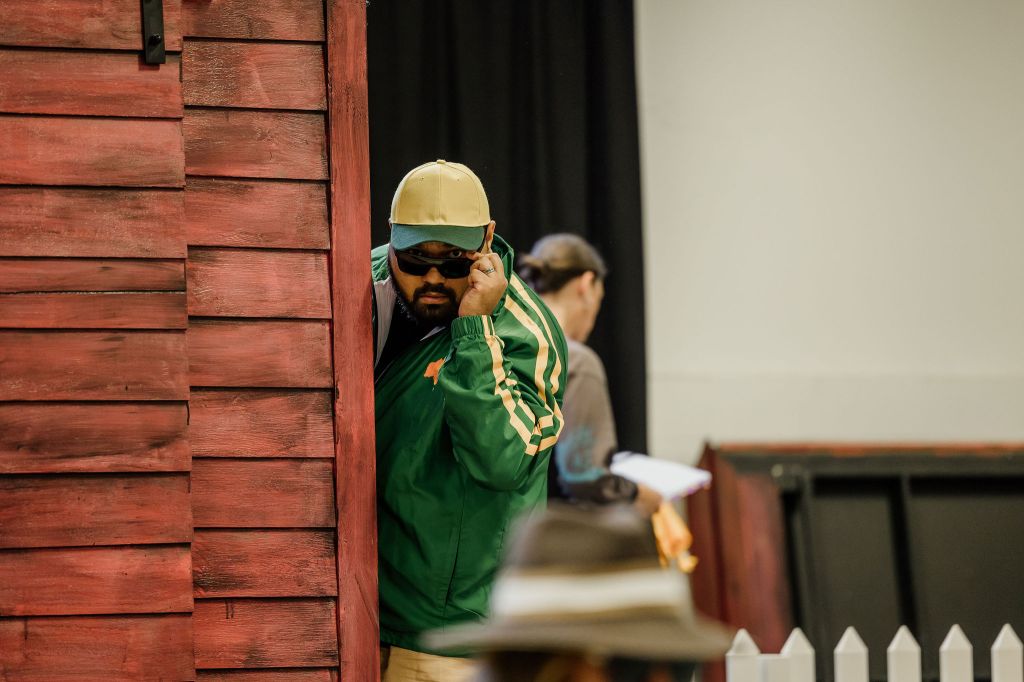

From the first mention of Scarpia’s name we hear the ominous sequence of three, strident chords that represent the evil character. Sung by Gevorg Hakobyan he emanates ruthlessness and amorality with a sinister voice and the actions of a disturbed man. This is highlighted in the powerful Te Deum sequence at the end of Act I where the power of the state is linked to that of the church and the choir sings along with Scarpia as he fantasises about his seduction of Tosca.

While Hakobyan conveys a narcissism and cruelty with a searing, caustic voice it is Young Woo Kim singing the role of Cavaradossi who was the standout performer of the opera with a powerful voice with which he conveyed a range of rich emotions along with a very honest portrayal of character.

The set in each of the acts is dominated by a large dome shape with an image of the virgin which works effectively and the oculus in the final act becomes the space from which Tosca plunges to her death.

In Act II the central feature of the set is Scarpia’s four poster bed which becomes the site of seduction as well as acting as a cage within which much of the strugglers between Scarpia and Tosca take place

The work really relies on its wonderful, evocative music, emotionally charged with some poignant orchestral passages which requires a conductor who is aware of that emotional and dramatic range. In Johannes Fritzsch and the Opera Australia Orchestra all the great qualities of the music were delivered.

With ten performances to go Tosca is one great reason for a short holiday across to Sydney.

Future operas at the Sydney Opera House

Brett Dean/ Matthew Jocelyn, Hamlet, July 20 – August 9

Mozart, Cosi van Tutte, August 1 – 17