Review by Malcolm Calder

Romeo and Juliet

By William Shakespeare

Auckland Theatre Company

Director – Benjamin Kilby-Henson

Design – Dan Williams

Lighting – Filament Eleven 11

Costumes – Daniella Salazar

Sound – Robin Kelly

With Ryan Carter, Liam Coleman, Theo Dāvid, Courteney Eggleton, Jesme Faa’auuga, Isla Mayo, Miriama McDowell, Phoebe McKellar, Jordan Mooney, Meramanji Odedra, Beatriz Romilly and Amanda Tito

Waterfront Theatre – until 9 August

Review by Malcolm Calder

This is a brave attempt by ATC to broaden its audience base and provide a path for younger performers. And when you’re doing that, a good Shakespeare is a fairly safe bet as it can probably do quite well with younger audiences, meet the needs of traditional adherents and will no doubt fare well with a schools audience. And ATC is to be acknowledged for that.

Unfortunately, when one looks at the larger theatrical picture, this Romeo and Juliet doesn’t really fare very well. Especially as a major production by one of this country’s more significant professional companies. However ATC’s production standards remain fairly high and are arguably this production’s saving grace.

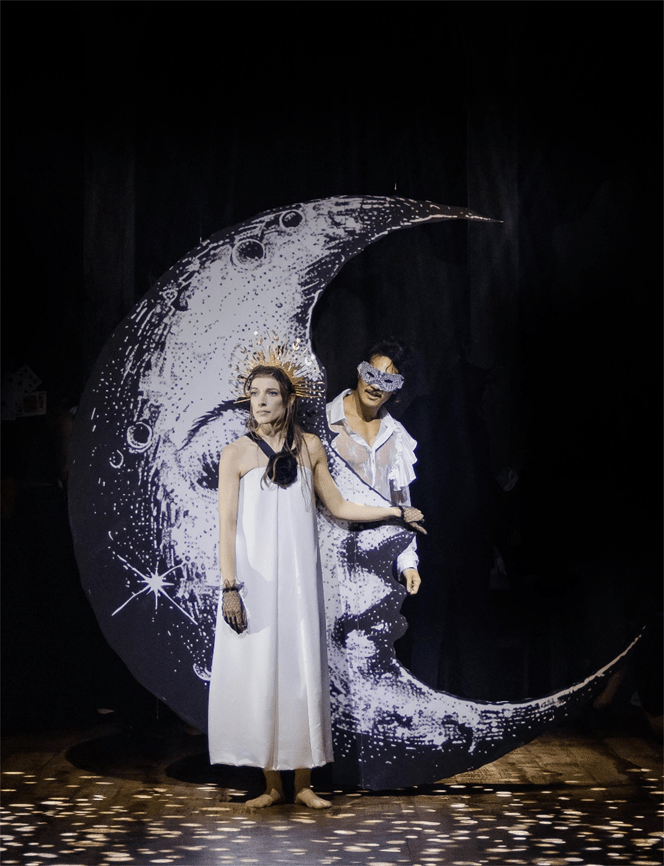

This Romeo and Juliet is set in a 1960s Verona and I get that – not such a silly idea. The the overall design is consistent and sometimes works very well indeed with the themes Director Benjamin Kilby-Henson is articulating – youth, love and lyricism. Chapeaus are due to the entire creative team and his production looks and feels quite stunning.

Dan Williams has generated a well-executed, three-dimensional set, largely articulated with reductive arches, derived some mobility from a well-used billiard table and unusually introduced what looks like a painter’s scaffold that trucks about a Veronian ballroom that is ‘under renovation’ and elsewhere too. It makes for a splendidly unusual balcony scene.

I wasn’t in Verona in the 1960s, however I did own a pair of vertically-striped trousers a decade later, so I give costumier Daniella Salazar’s costumes a big thumbs up too. Her use of colour is at times subtle and nuanced and the differences she has drawn between Montague and Capulet families are finely drawn. Of particular note is the ballroom scene.

But it was the lighting and the soundscape that were the standouts for me. The Filament 11 designers have introduced some dramatic and highly effective lighting that echoes the sentiments of Shakespeare’s words and the emotions highlighted by the director. It is also pleasing to see ATC using effective sound reinforcement for actors who often spend more time in front of cameras and on more intimate venues these days than on the comparatively largish Waterfront’s stage.

However, Miriama McDowell aside, the cast struggled with Shakepeare’s words, couplet-ridden though they are

In fact, the whole casting process seemed somehow – odd. Generational differences were blurred, there was a rather strange mix of accents, some characters seemed to fit the context while others didn’t, and I’m still trying to work out why there were so many varied approaches.

Music may be the food of love but, as the director has noted, poetic verse is its very life force. Romeo only addresses Juliet in verse and she does likewise. But sustaining this is very difficult indeed.

Apart from occasional flashes, especially with some of the longer speeches, the net result was one where authority and credibility were just – missing. At one point it seemed like I was watching a youth company of younger kiwis imagining a Verona they had never visited.

Miriama McDowell (Whaea Lawrence), however, was very much the exception, actually speaking Shakespeare’s words rather than matching the prevalent declamations of others. Theo Dāvid (Romeo) matched her to some extent leading one to wonder whether their work with the now-long-gone Popup Globe had anything to do with this.

There were a number of unanswered quibbles too: why, for example, did Friar Lawrence became a ‘Whaea’ in this production. If this really were set in 1960s Tauranga and there two gangs at war with each other it could make sense. But it is a term never uttered in in Verona in the 1960s. And perhaps a bit of undersheet nudity was a way of the simpering unreality of Paris, but that didn’t work for me either.

So thanks for the effort ATC. But Romeo and Juliet was a disappointment for me.