Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

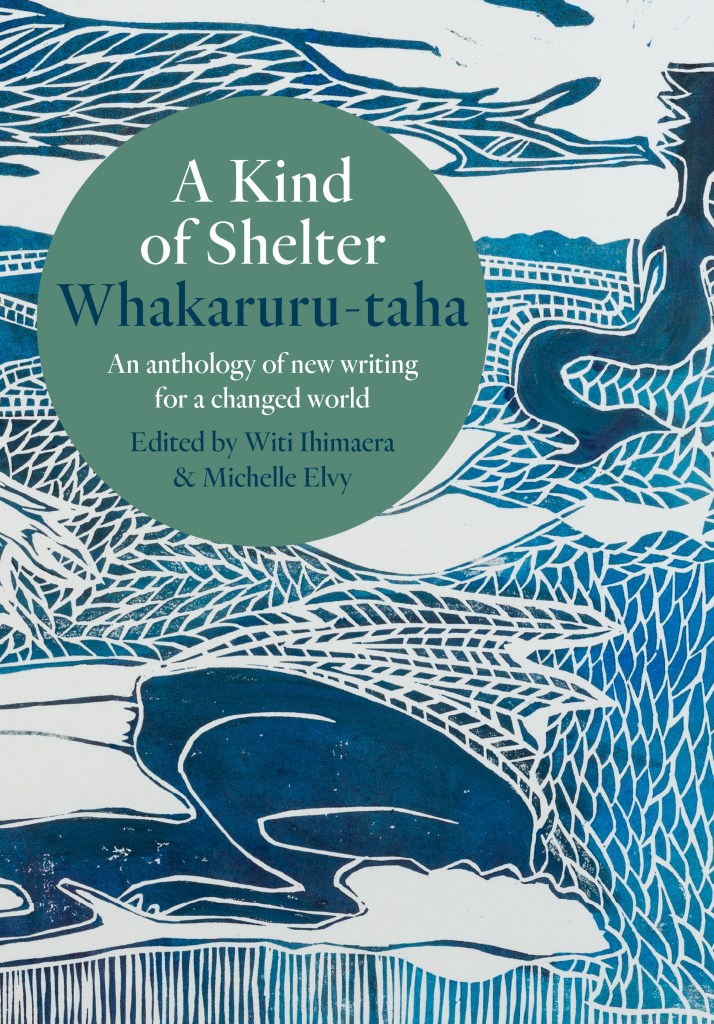

A Kind of Shelter Whakaruru-taha

An anthology of new writing for a changed world

Edited by Witi Ihimaera and Michelle Elvy

Massey University Press

RRP $39.99

Reviewed by John Daly-Peoples

In “A Kind of Shelter Whakaruru-taha” Witi Ihimaera and Michelle Elvy have brought together sixty-eight writers and eight visual artists, imagining them at a grand discussion group or hui where they share ideas about the future. These local and international artists include fiction and creative non-fiction writers as well as poets.

While the editors aim was to create a political and social framework which would engage with developing ideas about our future, the book is more of an eclectic set of voices who are variously, thoughtful, focussed, uncertain and tentative in their contemplation of the future. The various writings range from the intimate to the didactic, addressing the issues around past, present and future as the explore history, notions of indigeneity, climate change as well as social and political change. They all offer insights and guides to life which entertain, educate and inspire.

Some of the writers take on the serious social matters of the day like poets Essa Ranapiri and Michelle Rahurahu in their “Ram Raid” where the feelings and aspirations of youth escaping a rules-based society are linked to the actions of Tane in his separation of Earth and Sky.

One of Lisa Reihana’s photographs in the book also illustrated the myth of Ranginui and Papatūānuku with an image of the creation of the cosmos and moody brooding skies.

Then there are the joyous sounds of Ian Wedde’s “Tree House” with his description of the inner-city bird life with their human-like qualities while Cilla McQueen’s “Way Up South” with its panoramic description of Rakiora and references to Hone Tuwhare are eloquent explorations of the land and its history.

While many of the works are short pieces of writing some are more substantial as with “Ancestry, kin and shared history” a discussion with Dame Anne Salmond, Witi Ihimarea and the Brazilian indigenous, academic activist Apareceida Viaҫa which provides a wide ranging discussion on The Treaty, indigenous culture, as well as the thought-provoking differences between Māori and the Wari tribe of Brazil and their approaches to the environment , the animal world and their ancestors. According to Viaҫa most Amazonian people have no concept of ancestry.

In “Come and see it all the way from the town” Laura Jean McKay has written about similar themes which she previously developed in her book “The animals in that Country” exploring the natural world through the eyes and speech of animals and inanimate objects.

Among the more experimental works is Harry Ricket’s “Loemis song cycle: Epilogue” which follows the conception, production and performance of a requiem style musical work with five writers accompanied by an ensemble of musicians which explore a series of unrelated events, evoking ideas around transition, inevitability, optimism and infinity.

Through these writing the authors talk of journeys both physical and psychological, of crises such as Covid 19 along with other encounters and events which have shaped and changed their lives. Some writers dwell on the present, others on past histories and families which also become reflections on the future.

Wendy Perkins “At the Kauri Museum” where personal history and colonial history are tied to the history of the gun and kauri in shaping the land and society.

Another of the photographers included in the book is Yuki Kihara who represented New Zealand at last year’s Venice Biennale. with her work “Otamahua Quail Island” In the photographic series “Quarantine Islands” the artist dressed as “Salome” travelled across time uniting the various histories and forgotten stories of the islands with their connections to the Covid 19.covid pandemic.

Other writers include Alison Wong, Paula Morris, Tina Makereti, Ben Brown, David Eggleton, Hinemoana Baker, Erik Kennedy, Nina Mingya Powles, Gregory O’Brien, Vincent O’Sullivan, Patricia Grace, Selina Tusitala Marsh and Whiti Hereaka. Guest writers from overseas include Jose-Luis Novo and Ru Freeman.

To subscribe or follow New Zealand Arts Review site – www.nzartsreview.org.

The “Follow button” at the bottom right will appearand clicking on that button will allow you to follow that blog and all future posts will arrive on your email.

Or go to https://nzartsreview.org/blog/, Scroll down and click “Subscribe”.